Humanising Machines

One of the reasons why Machine Intelligence has taken off in recent years is because we have extraordinarily rich datasets that are collections of experiences about the world that provide a source for machines to learn from.

This essay is adapted from a transcript of the interview above. And was originally featured on Nell Watson's page here.

In the present age, Machine Learning is on the verge of transforming our lives. The need to provide intelligent machines with a moral compass is of great importance, especially at a time when humanity is more divided than ever. Machine Learning has endless possibilities, but if used improperly, it could have far-reaching and lasting negative effects.

Many of the ethical problems regarding Machine Learning have already arisen in analogous forms throughout history, and we will consider how, for example, past societies developed trust and better social relations through innovative solutions. History tells us that human beings tend not to foresee problems associated with their own development but, if we learn some lessons along the way, then we can take measures in the early stages of Machine Learning to minimize unintended and undesirable social consequences. It is possible to build incentives into Machine Learning that can help to improve trust through mediating various economic and social interactions. These new technologies may one day eliminate the requirement for state-guided monopolies of force and potentially create a fairer society. Machine Learning could signal a new revolution for humanity; one with heart and soul. If we can take full advantage of the power of technology to augment our ability to make good, moral decisions and comprehend the complex chain of effects on society and the world at large, then the potential benefits of prosocial technologies could be substantial.

THE EVOLUTION OF AUTONOMY

Artificial Intelligence (AI), which is also known as Machine Intelligence, is a blanket term that describes many different sub-disciplines. AI is any technology that attempts to replicate or simulate organic intelligence. The first type of AI in the 1950s and 1960s was essentially a hand-coded if/then statement (if condition “x,’ then do “y”). This code was difficult and time-intensive to program and made for very limited capabilities. Additionally, if the system encountered something new or unexpected, it would simply give an exception and crash.

Since the 1980s, Machine Learning has been considered a subset of AI whereby instead of programming machines explicitly, one introduces them to examples of what you want them to learn, i.e. ‘here are pictures of cats, and here are pictures of things like cats, but not cats, like foxes or small dogs.’ With time and through the use of many examples, Machine Learning Systems can educate themselves without needing to be explicitly taught. This is extremely helpful for two main reasons. First, hand coding is no longer necessary. Imagine trying to code a program to detect cats and not foxes. How do we tell a computer what a cat looks like? Breeds of cats can look quite different from one another. To do this by hand would be almost impossible. But with Machine Learning, we can outsource this process to the machine. Second, Machine Learning Systems have adaptability. If a new breed of cat is introduced, you simply update the machine with more data, and the system will easily learn to recognize the new breed without the need to reprogram the system.

More recently, starting around 2011, we have seen the development of Deep Learning Systems. These systems are a subset of Machine Learning and use many different layers to create more nuanced impressions that make them much more useful. It’s a bit like baking bread. You need salt, flour, water, butter, and yeast, but you can’t use a pound of each. They must be used in the correct proportion. These ingredients make simple bread if put together in the right amounts. However, with more variables, such as extra ingredients, and other ways to form the bread, you can make everything from a pain au chocolat to a biscotti. In a loose analogy, this is how Deep Learning compares to pure Machine Learning.

These technologies are very computationally intensive and require large amounts of data. But with the development of powerful graphics processing chips, this task has become much easier and can now be performed by something as small as a smartphone to bring machine intelligence to your pocket. Also, thanks to the internet, and the many people uploading millions of pictures and videos each week, we can create powerful sets of examples (datasets) for machines to learn from. The computing capacity and the data examples were critical prerequisites that have only recently been fulfilled and enabled this technology to finally be deployed, using algorithms invented back in the 1980s that were not usable at the time.

In the last two years, we have seen developments such as Deep Reinforcement Meta Learning, a subset of Deep Learning, where instead of learning as much as possible about one subject, a system tries to learn a little bit about a greater number of subjects. Meta-learning is contributing to the development of systems that can cope with very complex and changing variables and single systems that can navigate an environment, recognize objects, and have a conversation all at the same time.

THE BLIND HODGEPODGE MAKER

Despite the rapid advances in Machine Intelligence, as a society, we are not prepared for the ethical and moral consequences of these new technologies. Part of the problem is that it is immensely challenging to respond to technological developments, particularly because they are developing at such a rapid pace. Indeed, the speed of this development means that the impact of Machine Learning can be unexpected and hard to predict. For example, most experts in the AI space did not expect the abstract strategy game of Go to be a solvable problem by computers for at least another ten years. And there have been many other significant developments like this that have caught experts off guard. Furthermore, advancements in Machine Intelligence paint a misleading picture of human competence and control. In reality, researchers in the Machine Intelligence area do not fully understand what they are doing, and a lot of the progress is essentially based on ad hoc experimentation such that if an experiment appears to work, then it is immediately adopted.

To draw a historical comparison, humanity has reached the point where we are shifting from alchemy to chemistry. Alchemists would boil water to show how it was transformed into steam, but they could not explain why water changed to a gas or vapor, nor could they explain the white powdery earth left behind (the mineral residue from the water) after complete evaporation. In modern chemistry, humanity began to make sense of the phenomena through models, and we started to understand the scientific detail of cause and effect. We can observe a sort of transitional period where people invented models of how the world works on a chemical level. For instance, Phlogiston Theory was en vogue for nearly two decades, and it essentially tried to explain why things burn. This was before Joseph Priestley discovered oxygen. We have reached a similar point in Machine Learning as we have a few of our own Phlogiston type theories such as the Manifold Hypothesis. But we do not really know how these things work, or why. We are now beginning to create a good model and have an objective understanding of how these processes work. In practice that means we have seen examples of researchers attempting to use a sigmoid function and then, due to the promising initial results, trying to probe a few layers deeper.

For instance, Phlogiston Theory was en vogue for nearly two decades and it essentially tried to explain why things burn. This was before Joseph Priestley discovered oxygen. We have reached a similar point in machine learning as we have a few of our own Phlogiston theories, such as the Manifold Hypothesis. For instance, Phlogiston Theory was en vogue for nearly two decades, and it essentially tried to explain why things burn. This was before Joseph Priestley discovered oxygen. We have reached a similar point in Machine Learning as we have a few of our own Phlogiston type theories such as the Manifold Hypothesis. But we do not really know how these things work, or why. We are now beginning to create a good model and have an objective understanding of how these processes work. In practice that means we have seen examples of researchers attempting to use a sigmoid function and then, due to the promising initial results, trying to probe a few layers deeper.

Through a process of experimentation, we have found that the application of big data can bring substantive and effective results, although, in truth, many of our discoveries have been entirely accidental with almost no foundational theory or hypotheses to guide them. This experimentation without method creates a sense of uncertainty and unpredictability, which means that we might soon make an advancement in this space that is more efficient by orders of magnitude more than we have ever seen before. Such a discovery could happen tomorrow, or it could take another twenty years.

DISSENT AND DIS-COHESION

In terms of the morality and ethics of machines, we face an immense challenge. Integrating these technologies into our society is a daunting task. These systems are little optimization genies; they can create all kinds of remarkable optimizations or impressively generated content. However, that means that society might be vulnerable to deceit or counterfeiting. Optimization should not be seen as a panacea. Humanity needs to think more carefully about the consequences of these technologies as we are already starting to witness the effects of AI on our society and culture. Machines are often optimized for engagement, and sometimes, the strongest form of engagement is to evoke outrage. If machines can get results by exploiting human weaknesses and provoking anger, then there is a risk that they may be produced for this very purpose.

Over the last ten years, we have seen a strong polarization of our culture across the globe. People are, more noticeably than ever before, falling into distinctive ideological camps which are increasingly entrenched and distant from each other. In the past, there was a strong consensus on the meaning of morality and what was right and wrong. Individuals may have disagreed on many issues, but there was a sense that human beings were able to find common ground and ways of reaching agreement on the fundamental issues. However, today, people are increasingly starting to think of the other camps, or the other ideologies, as being fundamentally bad people.

Consequently, we are beginning to disengage from each other, which is damaging the fabric of our society in a very profound and disconcerting way. We’re also starting to see our culture being damaged in other ways as seen in the substantial amount of negative content that is uploaded to YouTube every minute. It’s almost impossible to develop an army of human beings in numbers sufficient enough to moderate that kind of content. As a result, much of the content is processed and regulated by algorithms. Unfortunately, a lot of those algorithmic decisions aren’t very good ones, and so quite a bit of content which is, in fact, quite benign, ends up being flagged or demonetized for mysterious reasons that can’t be explained by anyone. Entire channels of content can be deleted overnight, on a whim and with little oversight or opportunity for redress. There is minimum human intervention or reasoning involved in trying to correct unjustified algorithmic decisions.

This problem is likely to become a serious one as more of these algorithms get used in our society every day and in different ways. This may be potentially dangerous because it can lead to detrimental outcomes and situations where people might be afraid to speak out. Not because fellow humans might misunderstand them, although this is also an increasingly prevalent factor in this ideologically entrenched world, but because the machines might. For instance, a poorly constructed algorithm might select a few words in a paragraph and come to the conclusion that the person is trolling another person, or creating fake news, or something similarly negative.

The ramifications of these weak decisions could be substantial. Individuals might be downvoted or shadowbanned with little justification, and find themselves isolated, effectively talking to an empty room. As the reach of the machines expands, there flawed algorithmic decision systems have the potential to cause widespread frustration in our society. It may even engender mass paranoia as individuals start to think that there is some kind of conspiracy working against them even though they may not be able to confirm why they have been excluded from given groups and organizations. In short, an absence of quality control and careful consideration of the complex moral and ethical issues at hand may undermine the great potential of Machine Learning and its impact on the greater good.

COORDINATION IS THE KEY TO COMPLEXITY

There are certainly some major challenges to be overcome with Machine Learning, but we now have the opportunity to make appropriate interventions before potentially significant problems arise. We still have an opportunity to change course to overcome them, but it is going to be a real challenge. Thirty years ago, the entire world reached a consensus on the need to cooperate on CFC (chlorofluorocarbon) regulation. Over a relatively short period of a few years, governments acknowledged the damage that we were inflicting on the ozone layer. They decided that action had to be taken and, through coordination, a complete ban on CFCs was introduced in 1996, which quickly made a difference in the environment. This remarkable achievement is a testament to the fact that when confronted with a global challenge, governments are capable of acting rapidly and decisively to find mutually acceptable solutions. The historical example of CFCs should, therefore, provide us with grounds for optimism in the hope that we might find cooperative ethical and moral approaches to Machine Learning through agreed best practices and acceptable behavior.

Society must move forward cautiously and with pragmatic optimism in engineering new technologies. Only by adopting an optimistic outlook can we reach into an imagined better future and find a means of pulling it back into the present. If we succumb to pessimism and dystopian visions, then we risk paralysis. This is similar to the type of panic humans experience when they find themselves in a bad situation. It is akin to drowning in quicksand slowly. In this sort of situation, panicking is likely to lead to a highly negative outcome. Therefore, it is important that we remain cautiously optimistic and rationally seek the best way to move forward. It is also vital that the wider public be aware of the challenges, but also aware of the many possibilities that exist. Indeed, while there are many dangers in relying so heavily on machines, we must recognize the equally significant opportunities they present to guide us and help us be better human beings, to have greater power and efficacy, and to find more fulfillment and greater meaning in life.

DATASET IS DESTINY

One of the reasons why Machine Intelligence has taken off in recent years is because we have extraordinarily rich datasets that are collections of experiences about the world that provide a source for machines to learn from. We now have enormous amounts of data, and thanks to the Internet, there is a readily available source offering new layers of information that machines can draw from. We have moved from a web of text and a few low-resolution pictures, video, and location and health data, etc. And all of this can be used to train machines and get them to understand how our world works, and why it works in the way it does.

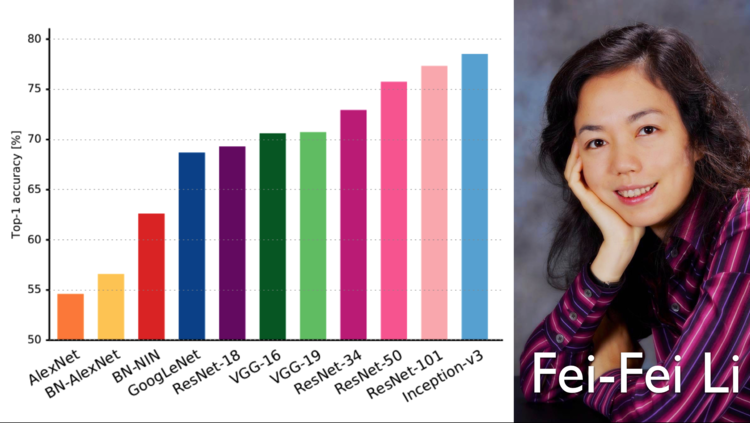

A few years ago, there was a particularly important dataset that was released, by a professor called Fei-Fei Li and her team. This dataset, ImageNet, was a corpus of information about objects ranging from buses and cows to teddy bears and tables. Now machines could begin to recognize objects in the world. The data itself was extremely useful for training convolutional neural networks that were revolutionary new technologies for machine vision. But more than that, it was a benchmarking system because you could test one approach versus another, and you could test them in different situations. This capability led to the rapid growth of this technology in just a few years. It is now possible to achieve something similar when it comes to teaching machines about how to behave in socially acceptable ways. We can create a dataset of prosocial human behaviors to teach machines about kindness, congeniality, politeness, and manners. When we think of young children, often we do not teach them right and wrong, but rather we teach them to adhere to behavioral norms such as remaining quiet in polite company. We teach them simple social graces before we teach them right and wrong. In many ways, good manners are the mother of morality and essentially constitute a moral foundational layer.

THE RISE OF THE MACHINES

There is a broader area of study called value alignment, or AI alignment. It is centered around teaching machines how to understand human preferences and how humans tend to interact in mutually beneficial ways. In essence, AI alignment is about ensuring that machines are aligned with human goals. We do this by socializing machines so that they know how to behave according to societal norms. There are some promising technical approaches and algorithms that could be used to accomplish this, such as Inverse Reinforcement Learning. In this technique machines can observe how we interact and decipher the rules without being explicitly told; effectively by watching how other people function. To a large extent, human beings learn socialization in similar ways. In an unfamiliar culture, individuals will wait for other people to start doing something like how to greet someone or which fork to use when eating. Children learn this way, so there are many great opportunities for machines to learn about us in a similar fashion.

Armed with this knowledge, we can move forward by trying to teach machines about basic social rules; like it isn’t nice to stare at people; or to be quiet in a church or a museum; or if you see someone drop something that looks important, you should alert them. These are the types of simple societal rules that we might ideally teach a six-year-old child. If this is successful, then we can move on to more complex rules. The important thing to remember is that we have some information that we can use to begin to benchmark these different approaches. Otherwise, it may take another twenty years to teach machines about human society and how to behave in ways that we prefer.

While the number of ideas in the field of Machine Learning is a positive sign, we cannot realize them in practice until we have the right quality and quantity of data. My nonprofit organization, EthicsNet, is creating a dataset of prosocial behaviors which have been annotated or labeled by people of differing cultures and creeds across the globe. The idea is to gauge as wide a spectrum of human values and morals as possible and to try to make sense of them so that we can find the commonalities between different people. But we can also recreate the little nuances or behavioral specificities that might be more suitable to particular cultures or situations.

Acting in a prosocial manner requires learning the preferences of others. We need a mechanism to transfer those preferences to machines. Machine intelligence will simply amplify and return whatever data we give it. Our goal is to advance the field of machine ethics by seeding technology that makes it easy to teach machines about individual and cultural behavioral preferences.

There are very real dangers to our society if one ideologically-driven extremist group ever gains supremacy in establishing a master set of values for machines. This is why EthicsNet needs to continue its mission to enable a plurality of values to be collected and mapped and for a “passport of values” that will allow machines to meet our personal value preferences. Heaven help our civilization if machine values were ever to be monopolized by extremists. Many individuals and groups in the coming years will attempt to develop this as a deadly weapon. It is the ultimate cudgel to smash dissent and ‘wrongthink’. As a global community, we must absolutely resist any attempt to have values forced upon us via the medium of intelligent machines. This is a time of intense polarization and extremist positions when there is tremendous temptation to press for an advantage for one’s own tribe. Safeguarding a world where a plurality of values is respected requires the earnest efforts of people with noble, dispassionate, and sagacious characters.

TRUST MAKES COORDINATION CHEAP

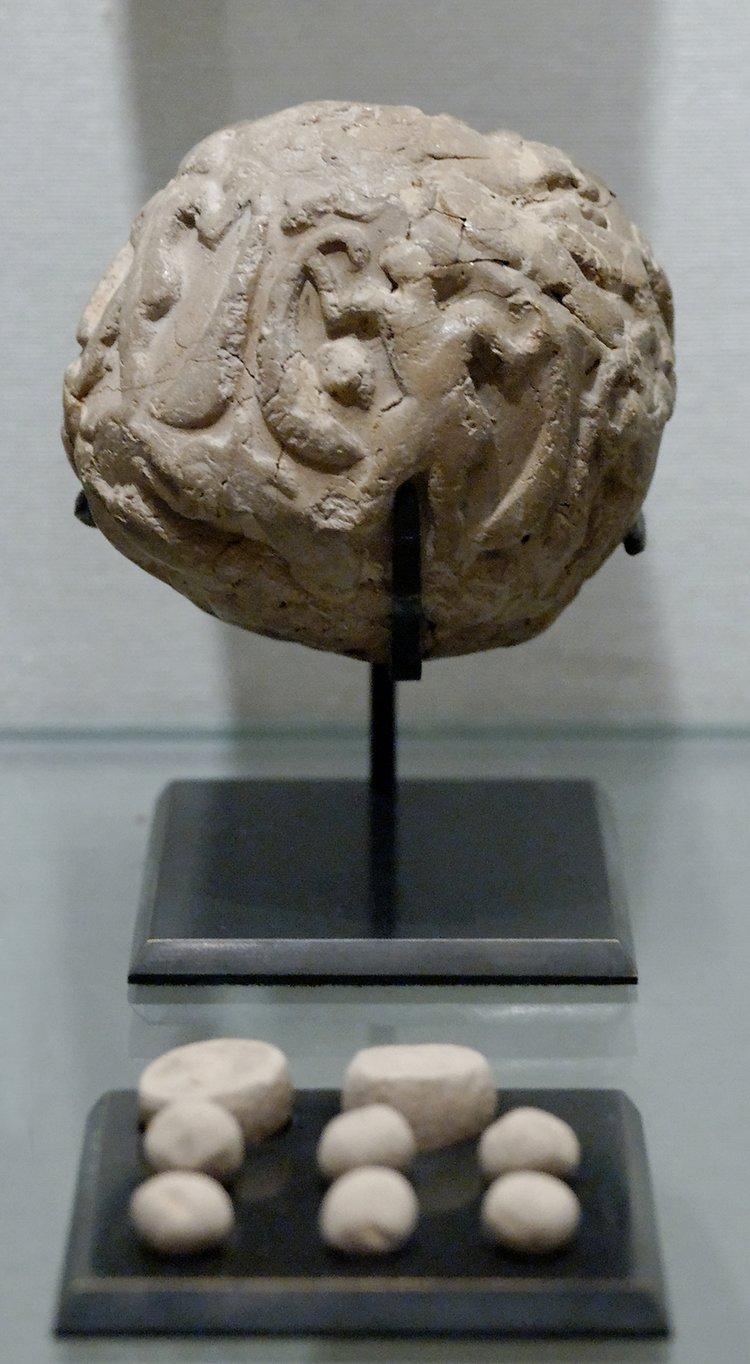

Human beings have been using different forms of encryption for a very long time. The ancient Sumerians had a form of token and crypto solution, 5,000 years ago. They would place these literal small tokens, that represented numbers or quantities, inside a clay ball (a Bulla). This meant that you could keep your message secret, but you could also be sure that it had not been cracked open, for people to see, and the tokens would not get lost. Now, 5,000 years later, we are discovering a digital approach to solving a similar problem, so what appears to be novel is in many ways an age-old theme.

One of the greatest developments of the Early Renaissance was the invention of double-entry accounting, created in two different locations during the 10th and 12th centuries. Nevertheless, the idea did not reach fruition until a Franciscan friar, called Father Luca Pacioli, was inspired by this aesthetic that he saw as a divine mirror of the world. He thought that it would be a good idea to have a “mirror” of a book’s content, which meant that one book would contain an entry in one place, and there would be a corresponding entry in another book. Although this appears somewhat dull, the popularisation of the method of double-entry accounting actually enabled global trade in ways that were not possible before. If you had a ship at sea and you lost the books, then all those records were irrecoverable. But with duplicate records you could recreate the books, even if they had been lost. It made fraud a lot more difficult. This development enabled banking practices, and, eventually, the first banking cartels emerged, which, otherwise, would not have been possible. One interesting example is the Bank of the Knights Templar, where people could deposit money in one place and pick it up somewhere else; a little bit like a Traveler’s Cheque. None of this would have been possible if we did not have distributed ledgers.

Several centuries later, at the Battle of Vienna in 1683, the Ottomans invaded Vienna for the second time, and they were repulsed. They went home in defeat, but they left behind something remarkable. A miraculous substance, coffee. Some enterprising individuals took that coffee and opened the first coffeehouse in Vienna. And, to this day, Viennese coffee houses have a very long and deep tradition where people can come together and learn about the world by reading the available periodicals and magazines. In contrast to a different trend of inebriated people meeting in the local pub, people could have an enlightened conversation. Thus coffee, in many ways, helped to construct the Enlightenment because these were forums where people could share ideas in a safe place that was relatively private. The coffee house enabled new forms of coordination which were more sophisticated. From the first coffee houses, we saw the emergence of the first insurance companies, such as Lloyds of London. We also saw the emergence of the first joint stock companies, including the Dutch East India Company. The first stock exchange in Amsterdam grew out of a coffee house.

This forum for communication, to some extent, enabled the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution was not so much about steam. The Ancient Greeks had primitive steam engines. They might even have had an Industrial Revolution from a technological perspective, but not from a social perspective. They did not yet have the social technologies required to increase the level of complexity in their society because they did not have trust-building mechanisms or the institutions necessary to create trust. If you lose your ship, you do not necessarily lose your entire lifestyle. If you are insured, that builds trust which in turn builds security. In a joint stock company, those who run a company are obliged to provide shareholders with relevant performance information. The shareholders, therefore, have some level of security that company directors cannot simply take their money – they are bound by accountability and rules, which helps to build trust. Trust enables complexity, and greater complexity enabled the Industrial Revolution.

NEVER OUTSOURCE THE ACCOUNTING

Today, we have remarkable new technologies built on triple-entry ledger systems. These triple-entry ledger technologies mean that we can build trust within society and use these as layers of trust-building mechanisms to augment our existing institutions. It is also possible to do this in a decentralized form where there is, in theory, no single point of failure and no single point of control or corruption within that trust-building mechanism. This means we can effectively franchise trust to parts of the world that don’t have reliable trust-building infrastructures. Not every country in the world has an efficient or trustworthy government, and so these technologies enable us to develop a firmer foundation for the social fabric in many parts of the world where trust is not typically strong.

Trust-building technology is a positive development, not only for commerce but also for human happiness. There is a strong correlation between happiness and trust in society. Trust and happiness go hand-in-hand, even when you control for variables, such as Gross Domestic Product. If you are poor, but you believe that your neighbor generally has your best interest at heart, you will tend to be happy and feel secure. Therefore, anything that we can use to build more trust in society will typically help to make people feel happier and secure. It also means that we can create new ways of organizing people, capital, and values in ways that enable a much greater level of complex societal function. If we are fortunate and approach this challenge in a careful manner, we might discover something like another Industrial Revolution, built upon these kinds of technologies. Life before the Industrial Revolution was difficult, and then it significantly improved. If we look at human development and well-being on a long scale, basically nothing happened for millennia, and then there was a massive improvement in well-being occurred. We are still reaping the benefits of that breakthrough to the serve the needs of the entire world, and we have increasingly managed to accomplish this as property rights and mostly-free markets have expanded.

However, there have also been certain negative consequences of economic development. Today, global GDP is over 80 trillion dollars, but we often fail to take into account the externalities that we’ve created. In economic terms, externalities are when one does something that affects an unrelated third party. Pollution is one example of an externality. Although world GDP may be more than 80 trillion dollars, there are quadrillions of dollars of externalities which are not on the balance sheet. Entire species have been destroyed and populations enslaved. In short, there have been many unintended consequences and second and third-order effects which have not been accounted for. To some extent, a significant portion of humanity has achieved all the trappings of a prosperous, comfortable society by not paying for these externalities. But it’s generally done ex post facto or after the fact. Historically, we have had a tendency to create our own problems through lack of foresight and then tried to correct them after inflicting the damage. However, as machine ethics technologies get more sophisticated, we are able to intertwine them with Machine Economics technologies, such as distributed ledger technology and machine intelligence, to connect and integrate everything together to better understand how one area affects another. We will in the 2020s and 2030s be able to start accounting for externalities in society for the very first time. This means that we can include externalities in pricing mechanisms to make people pay for them at the point of purchase, not after the fact. And this means that products or services that don’t create so many externalities in the world will, all things being equal, be a little bit cheaper. We can create economic incentives for people to be kinder to one another while achieving a profit, and thus overcome the traditional dichotomy between socialism and capitalism. We can still realize the true benefits of free markets if we follow careful accounting practices that consider externalities. That is what these distributed ledger technologies, along with Machine Ethics and Machine Intelligence, are going to enable via the confluence of the three elements coming together.

POWER AND PERSUASION

The potential of the emerging technologies is such that it is not inconceivable that they may even be able to supplant states’ monopoly of force in the future. We would have to consider whether or not this would be a desirable step forward as not all states could be trusted to use their means of coercion in a safe, responsible manner, even now, without the technology. States exist for a reason. If we look at the very first cities in the world, such as Çatalhöyük in modern day Turkey, these cities do not look like modern cities at all and are more akin to towns by comparison to contemporary scales and layout. They are more similar to a beehive in that they are built around little, square dwellings, all stacked on top of each other. There are no streets, no public buildings, no plazas, no temples, or palaces. All the buildings are identical. The archaeological record, tells us that people started to live in these kinds of conurbations for a while, and then they stopped for a period of about 800 years. They gave up living in this way, and they went back to living in very small villages, in little huts and more primitive dwellings. When we next see cities emerge, they are very different. In these next cities, such as Uruk and Babylon, boulevards, great temples, and workshops begin to take shape. We also observed the development of specific sections of the city with certain industries and commercial areas. On a functional level, they were not too dissimilar from modern cities; at least in their general layout and in terms of the different divisions of labor that existed. So, what was the real difference and why did people abandon cities for a time? If we consider that these were really nomadic societies where individuals and groups moved from place-to-place, then it is easier to understand that territory, and personal possessions were not tied to a fixed location. Nomads had to take their property with them when they moved. So, these were very egalitarian societies where no single person had much more than anyone else. Subsequently, these nomadic people started living together and began farming. Farming changed the direction of human development as we know it because it enabled people to turn one “X” of effort into ten “Y” of output. As farming progressed, some individuals enjoyed greater success in production output than others. This allowed them to accumulate more possessions and accrue greater wealth than their neighbors. These evolving inequalities engendered a growing tension in society, people started resenting one another, and it became necessary to find ways of protecting private property given the increasing risk of theft. This, in turn, necessitated the evolution of collective forms of coercion and the gradual evolution of the state. In its earliest forms, clans would protect themselves through the collective, physical protection of their territory and possessions. It was the evolution of centralized power that enabled cities in their modern form and why the first cities that had yet to develop this social technology failed.

10,000 years later we still have the same social technology, centralization of power, and monopoly of force that generally governs the world. The state also enables order and has helped foster civilized society as we know it, so it can certainly be adaptive for the stability of civilization. Nonetheless, the technologies we are now developing may enable us to move beyond monopolies of force and, paradoxically, return to a way of life that is a little bit more egalitarian. Outcomes might potentially be less zero-sum in character; where it’s less about winning and losing and more about trade-offs. Generally speaking, trade can enable non- zero-sum outcomes. If I want your money more than you want those sausages, then the best solution is a trade-off. As we develop more sophisticated trading mechanisms, including Machine Economics technologies, we can begin to trade all kinds of goods. We can trade externalities, and we can even pay people to behave in moral ways or make certain value-based decisions. We can begin to incentivize all kinds of desirable behaviors by using the carrot instead of the stick.

MACHINE ECONOMICS

Yet, for all the successful implementation of distributed ledger and blockchain technologies, the question of trust is still of central importance. In the current wild west environment, one of the most important aspects of trust in this space is actually knowing other people. Who are the advisors of your crypto company? Do you have some reliable individuals in the organization you can count on? Are they actually involved in your company? These are the questions that people want answers to, along with a close examination of your white paper (the document that typically functions as a ‘business plan’, merged with a technical overview). Most people lack the level of expertise required to really make sense of mathematics. Even if they do have that expertise, they will have to vet a lot of code, which can be revised at any time. In fact, even in the crypto world, so much of the trust is built on personal reputation. Given that we are at an early stage of development in Machine Economics (e.g. Blockchain), these technologies are only likely to achieve substantive results when they are married with machine intelligence and machine ethics. Such holistic integration will facilitate a new powerful form of societal complexity in the 2020s. The first Industrial Revolution was about augmenting the muscle of beasts of burden and human beings and harnessing the mode of power. The second Industrial Revolution – the Informational Revolution, was about augmenting our cognition. It enabled us to perform a wide variety of complex information processing tasks and to remember things that our brains would not have the capacity for. That is why computers were initially developed. But we are now on the verge of another revolution, an augmentation of what might be described as the human heart and soul: augmenting our ability to make good moral judgments; augmenting our ability to understand how an action that we take has an effect on others; giving us suggestions of more desirable ways of engaging. For example, we might want to think more carefully about our everyday actions such as sending an angry email to a particular individual.

THE INDUSTRIALIZATION OF HAPPINESS

If we can develop technologies that encourage better behavior and might be cheaper and kinder to the environment, then we can begin to map human values and map who we are deep in our core. These technologies might help us build relationships with people that we otherwise might have missed out on. In a social environment, when people gather together, the personalities are not exactly the same, but they can complement each other. The masculine and the feminine, the introvert and the extrovert, the people who have different skills and talents, and possibly even worldviews, can share similar values. So, individuals are similar in some ways, and yet, different. In your town, there may be a hundred potential close friends. But unless you have an opportunity to meet them, sit down for coffee with them, and get to know them, you pass like ships in the night and never see each other, except for maybe an occasional tip of your hat to them. These technologies can help us find people that are most like us. As Timothy Leary entreated us, “find the others.” Machines can help us find others in a world where people increasingly feel isolated. During the 1980s, statistically, many of us could count on three or four close friends. But today, people often report having only one or no close friends. We live in a world of incredible abundance, resources, safety and opportunities. And yet, many people feel disconnected from each other, themselves, spirituality and nature.

By augmenting the human heart and soul, we might be able to solve those higher problems in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs; to help us find love and belonging, build self-esteem and lead us towards self-actualization. There are very few truly self-actualized human beings on this planet, and that is lamentable because when a human being is truly self-actualized, their horizons are limitless. So, it will be possible to build in the 2020s and beyond, a system that does not merely satisfy basic human needs but supports the full realization of human excellence and the joy of being human. If such a system could reach an industrial scale, everyone on this planet would have the opportunity to be a self-actualized human being.

However, while the possibilities appear boundless, the technology is developing so rapidly that non-expert professionals, such as politicians, are often not aware of it and how it might be regulated. One of the challenges of regulation is that it is generally done in hindsight. A challenge appears, and political elites often respond to it after the fact. Unfortunately, it can be exceedingly difficult to keep up with both technological and social change. It can also be difficult to regulate in a proactive way rather than a reactive way. That is one of the reasons why principles are so important because principles are the things that we decide in advance of a situation. So, when that situation is upon us, we have an immediate heuristic process of how to respond. We know what is acceptable and what is not acceptable, and if we have sound principles in advance of a dilemma, we are much less likely to accidentally make a poor decision. That is one of the main reasons why having good principles is so important.

AI-BERMENSCH

Admittedly, we have to consider how effectively machines might interpret values; they might be very consistent even though we, as humans, may perhaps see grey areas, not only black and white. We might even engineer machines that on some levels, on some occasions, are more moral than the average human being. The psychologist, Lawrence Kohlberg, reckoned that there were about six different layers of moral understanding. . It is not about the decision that you make but rather the reason why you make that decision. In the early years of one’s life, you learn about correct behavior and the possibility of punishment. As you grow older, you learn about more advanced forms of desirable behavior such as being loyal to your family and friends or recognizing when an act is against the law or against religious doctrine. When considering the six levels, Kohlberg reckoned that most people get to about level four or so, before they pass on. Only a few people ever manage to get beyond that. Therefore, it may be the case that the benchmark of average human morality is not set that high. Most people are generally not aspiring to be angels; they are aspiring to protect their own interests. They are looking at what other people are doing and trying to be as moral as they are. This is essentially a keeping-up-with-the-Joneses morality. Now, if there are machines involved, and the machines are helping to suggest potential solutions that might be a tad more moral than many people have the ability to reason with, then perhaps machines might add to this social cognition of morality. It is thus possible that machines might help tweak and nudge us in a more desirable moral direction. Although, given how algorithms can also take us in directions that can be very quietly oppressive, it remains to be seen how the technology will be used in the near future. People will readily rebel against a human tyrant or oppressor that they can point at, but they don’t tend to rebel against repressive systems. They tend to passively accept that this is the way things work. That is why it is important for such technologies to be implemented in an ethical manner and not in a quietly tyrannical way.

Finally, the development of Machine Learning may depend, to some extent, on where the technological breakthroughs are made. Europe has a phenomenal advantage with these new technologies. There is a deep well of culture, intellect, and moral awareness in the history of the European continent. We have a remarkable artistic, architectural and cultural heritage and, as we begin to introduce machines to our culture, as we begin to teach these naive little agents about society and how to socialize, we can make a significant difference. Europe has a uniquely positioned opportunity to be the leader in bringing culture and ethics into machines given our long heritage of developing these kinds of technologies. While the U.S. tends to think in terms of scale, and China can produce prototypes at breakneck speed, Europeans tend to think deep in terms of meaning and happiness. We tend to think more holistically and understand how things connect and how one variable might relate to another. We have a deep and profound understanding of history because Europe has been part of so many different positive and negative experiences. Consequently, Europeans have a slightly more cautious way of dealing with the world, and we approach most things with caution and forethought as the essential ingredients in doing something right way. Europe has a monumental opportunity to be the moral and cultural leader of this new AI wave that will rely heavily on machine economics and machine ethics technologies.

To conclude, Machine Learning promises to transform social, economic and political life beyond recognition during the coming decades. History has taught us many lessons, but if we do not heed them, we run the risk of making the same mistakes over and over again. As technology develops at a rapid rate, it is critical that we get a better understanding of our experiments and develop rational and moral perspective. Machine Learning can bring many benefits to humanity. However, there is also the potential for misuse. There is a tremendous need to infuse technology with the ability to make good moral judgments that can enrich our social fabric.

ExO Insight Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.